Hiten Bawa, an architect and artist, is passionate about both his careers. Even so, he concedes that he prefers art; that being an artist is “a part of his nature that he cannot suppress or run away from”.

Bawa, who is profoundly deaf and lives with bilateral cochlear implants, challenges our preconceived notions about people with disabilities. His experience of living with deafness, along with his passion for architecture, and the exploration of his Indian identity are constant themes in his artwork. They often feature architectural elements, street -maps, sign language and references to Indian culture as seen in Lenasia – Musti Mudra, the painting featured above.

BIOGRAPHY

Hiten Bawa was born in Johannesburg in 1988 and spent his formative years in the Indian townships of Roshnee and Lenasia. When he was a year old, Bawa suffered a childhood illness which led to his hearing impairment. His parents recognised his talent for drawing and sent him to the Johannesburg Art Foundation when he was 10. Later, Bawa attended high school at The National School of the Arts, where he furthered his art education. After matriculating, he studied Architecture, eventually obtaining a Masters Degree from UCT.

In 2015 Bawa was a finalist in the SA Taxi Awards. Since then he has completed artist residencies in Japan, Finland and Spain and exhibited his work at numerous shows. Several of his artworks now belong to the J P Morgan Chase Art Collection. Bawa also runs his own architectural practice which specialises in creating spaces for those with disabilities and special needs.

HIS WORK

As an artist, Hiten Bawa works in various styles and with all types of media, which allows him to explore a range of ideas and concepts. His works include digital prints, acrylic painting, watercolors and pen drawings.

The artwork above, A Guide to Johannesburg Taxi Hand Signs, is derived from Bawa’s acclaimed entry for the S A Taxi Awards. He was inspired by the idea of connecting sign language; with the unique hand signs that taxi users in South Africa have developed; to indicate their chosen destinations to drivers. Following the competition, Bawa created decals of his artwork which were featured on several taxis. In this illustration, Bawa has named some of the popular destinations in Johannesburg along with their corresponding hand signal. Each sign is further overlaid with a street map of that area.

Taxi hand signs are something many of us do not pay much attention to, but Bawa invites us to examine them anew. He creates a meaningful connection between taxi hand signs and the sign language used by the deaf. Those of us without hearing problems also use our gestures and bodies to communicate with each other, but we do not necessarily appreciate the significance of this non-verbal communication in the way that the deaf do.

For her book on Bharatanatyam, Insights and Impressions, Sureka Singh, a local dance teacher, commissioned Bawa to illustrate the various postures, facial expressions and hand gestures (mudras) involved in this traditional dance.

Bawa says, “My sense of sight is heightened to compensate for the lack of hearing… I became more perceptive of body language, movements and hand gestures. I realised I can understand the Bharatanatyam hand gestures, as they communicate concepts and stories in a similar manner to South African sign language,” (Waterworth, 2019). This connection to dance inspired Bawa to create a series of paintings incorporating Indian dance, the symbolic hand gestures of Bharatanayam and sign language.

For Bawa, it is important to reflect his heritage and culture in his art….indeed as he rightly notes “no artist can paint a neutral-themed work without referencing… his/her identity, beliefs, emotions, influences and background”.

It took many years before Bawa was comfortable embracing references to his Indian heritage in his work. This is a common struggle experienced by many young Indian artists who want to create modern, contemporary artworks while reflecting who they are and where they come from. Bawa gradually realised that people wanted to see work from his perspective, rather than subjects that he had no personal connection to. He believes that his ‘Indian dancer’ series and some of his religious-themed commissions are an indication that the Indian community have a renewed interest in their culture and heritage.

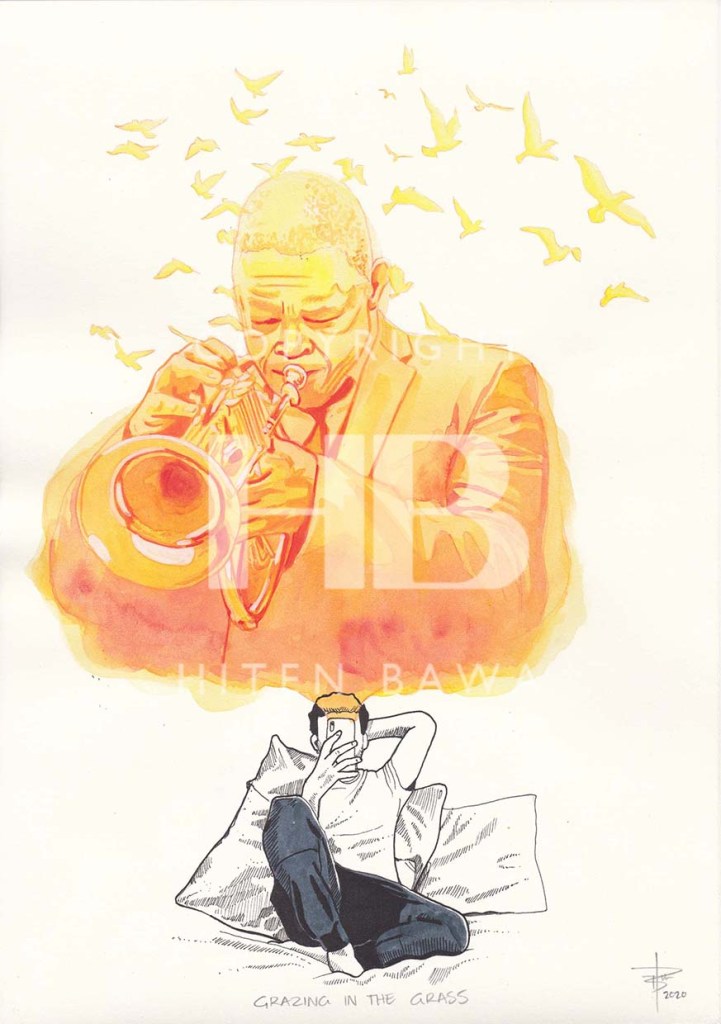

The title of the painting Grazing in the Grass (below) refers to a famous song by South African musician Hugh Masekela. In the painting Bawa is shown listening to Masekela’s music on his phone. As a deaf person growing up in a silent world, Bawa was not expected to develop any taste in music but the cochlear implants now allow him to hear. During the lockdown caused by the Covid pandemic, he listened to many different genres of music and has developed a great appreciation for timeless music.

While the drawing of Bawa, leaning against his pillows is monochromatic, the image of Masekela playing the trumpet while surrounded by birds is shown in a burst of colour. This is an apt way to understand how music can change silence to create beauty and connections; and to transport us into other worlds. Those who are deaf or have hearing disabilities are denied this pleasure, which many of us take for granted. Bawa’s painting of his own experience raises our awareness by allowing us a glimpse into his world.

Bawa painted Senso-ji Temple Asakusa, during his residency in Japan. It is a reflection of the architecture and culture that he experienced while living there. The central figure in the image is of a woman in traditional geisha dress holding an umbrella. She stands in the rain waiting to cross the street. Surrounding her are other shadowy figures also holding umbrellas. A portion of the Senso-ji Temple, one of the oldest and most popular temples in Tokyo, looms above all the figures. In the top left is a hand gesture used by Buddhists while meditating, this one symbolising ‘dimension’. The gesture refers to the spiritual nature of the space.

All these elements coalesce to create a unique sense of place, and conjure up an evocative memory of a rainy evening in Japan.

Some of the common themes that feature in Bawa’s recent work are the exploration of a South African Indian identity, the Indian diaspora and the social inequalities and injustices which are the legacy of Apartheid. These issues are viewed through the lens of those who live with disabilities and special needs.

Art should challenge your bodies (sic) and minds by forcing you to see the world through a different perspective. My personal experiences, interactions with diverse groups of people especially people with disabilities and places inspire me to create (Bawa).

Those of us who are physically able are often unaware of the struggles of those with disabilities or other afflictions. In sharing his life experiences and observations through his artwork, Bawa reminds us that we have more in common with each other than we think. The subjects close to his heart – dance, music and art are some of the ways in which everyone communicates, regardless of their individual status.

RESOURCES

*All illustrations appear with Bawa’s copyright & watermark.

Bawa H. Email interview. Oct 2020.

hitenbawa.co.za

Waterworth T. The Independent on Saturday, Aug 2019.

Alix-Rose Cowie, Between 10 &5. Aug 2014 (10and5.com)

Amazing talent!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent info. Great to see young artists being recognized and pursuing their bliss. Talented young man. Keep at it. Love your work.

LikeLiked by 1 person